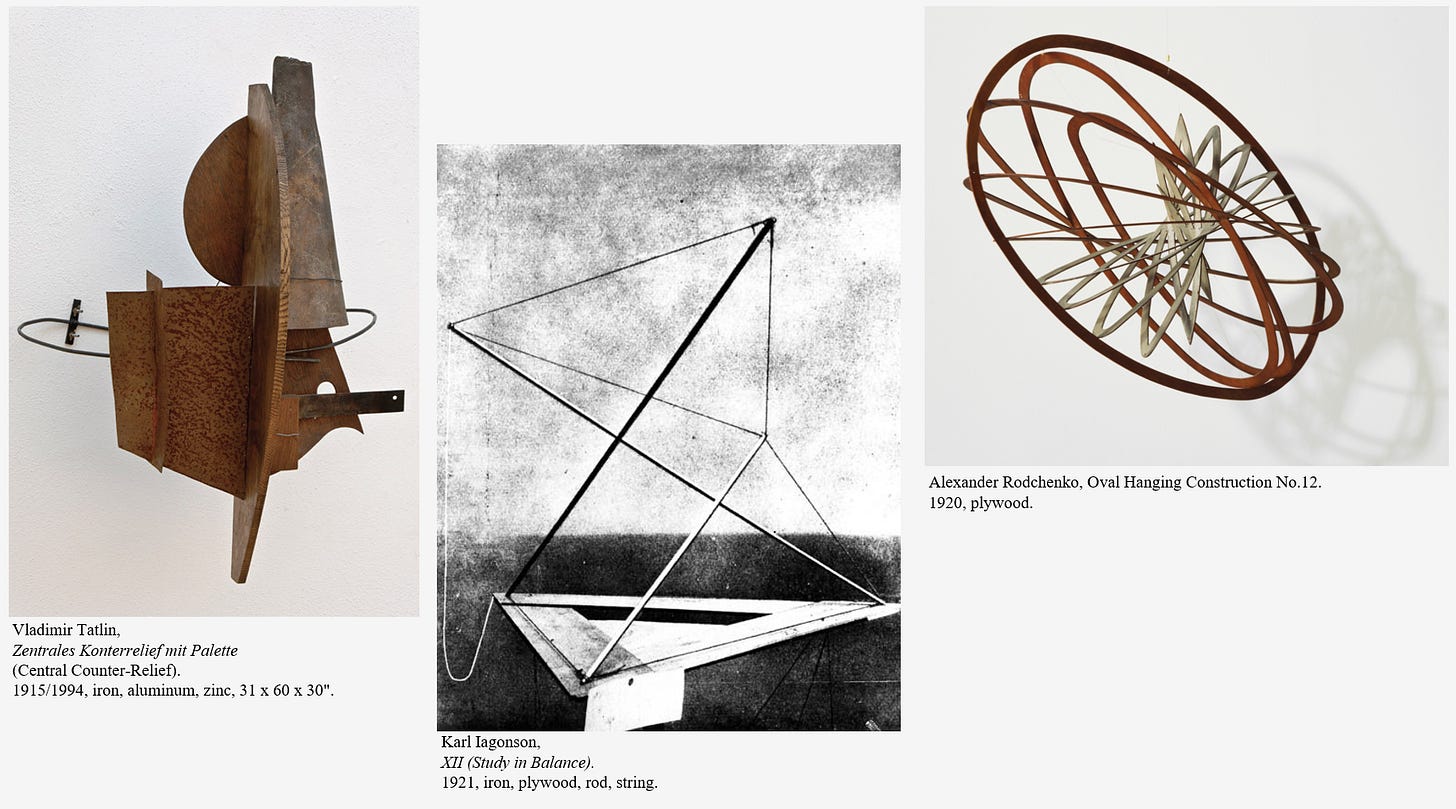

I’ve made a video the other day about Constructivism and love. My overall argument was something like this: constructivist works of art may serve as visual metaphors for a dynamic building of meaningful relationships.

Constructivism is not charming. Yet it still appeals to your aesthetic sensibility, your capacity to both judge and feel, to extend yourself beyond yourself and meet an artistic form foregrounded by another human being. These artists wanted to explore the aesthetic capabilities of industrial materials that would allow Art to play an important role in the building of the new state. They looked for radically different forms that could speak the language of their historical moment.

Be it through their small scale, structural instability, or glaring purposelessness, these objects give artistic form to a socio-historical problem.

I find these works beautiful because of their material fragility and conceptual ambition. And as all that is beautiful, they too have that peculiar healing-balm effect on the (broken) heart.

To be fair, constructivists couldn't care less about your broken little heart. They were revolutionaries plugged into the process of forging a new state. This art form was to engage with its rapidly transforming historical moment.

According to one of the movement’s pioneers, Aleksey Gan, only Constructivism could adequately respond to the abrupt shifts and strides that underpin the process of building Soviet Communism. Industrially underdeveloped, post-revolutionary Russia struggled to separate itself from its Imperial past (while retaining its imperial territorial integrity). The abrupt break with its history and a leap forward into the Socialist future was at the center of much of the economic and cultural policies of the first post-revolutionary years. These shifts and strides sped up by the Soviet ideologues were partly fueled by their generalized reading of Karl Marx.

No matter your political preferences, I think everyone should read Marx. Unlike your run-of-the-mill, self-proclaimed, first-world Marxist, Marx is quite funny and multi-dimensional. And, beside his political and economic treatise, Marx understood a thing or two about love.

Apart from manifestos, manuscripts, volumes, and essays on the monstrosities of capitalism and the promises of communism, Marx penned a different kind of texts. In his early years, he wrote love poems to Jenny Westphalen, later his wife. Here is one such poem, “To Jenny”, from 1836.

See! I could a thousand volumes fill,

Writing only “Jenny” in each line,

Still they would a world of thought conceal,

Deed eternal and unchanging Will,

Verses sweet that yearning gently still,

All the glow and all the Aether’s shine,

Anguished sorrow’s pain and joy divine,

All of Life and Knowledge that is mine.

I can read it in the stars up yonder,

From the Zephyr it comes back to me,

From the being of the wild waves’ thunder.

Truly, I would write it down as a refrain,

For the coming centuries to see—

LOVE IS JENNY, JENNY IS LOVE’s NAME

Marx is 18 when he writes this. I do not mean to overstate the importance of his poems. Reportedly, he looked back at his poetry youth as one should: with a tolerant smile and a healthy dose of humor.

But, some scholars see in this poem an early articulation of the relationship between the particular and the universal (a dialectic central to Marx’s thought). Art Historian Elise Archas, for example, in the coda to her book on performance art, offers this reading of Marx’s love poem.

Archias writes that “To Jenny” …

connects the specific person to an expansive notion of love. Jenny’s name alone evokes “pain,” “joy divine,” and “All of LIfe and Knowledge that is mine” because for the singer “JENNY IS LOVE’s NAME.” The poem pairs self-affirmation with an invitation to “See!” a wider “world of thought,” aware that the feeling for the specific Jenny matters only insofar as it connects the lover with the reader’s love–with all love at the moment of recognizing itself among the objective forces of nature. Whether writing about love in this early example, or later, about history, “species being,” labor, communism, or need as “the first premise of all human experience,” Marx constantly works up notions that intertwine generalizing concepts with concrete particularity, asking us to think on both registers simultaneously …

(emphais mine)

This ability to think both universal and in particular is at the center of Marx's most compelling writing. Constructivists seem to understand this and give form to this complex, dynamic idea.

How can an artwork that engages the industrial concerns of its time give form to such thinking? In the video, I speak about Karl Iagonson’s XIII.

The universal here is the set of natural laws of gravity and tension, the properties of material objects in real space, unchanged and kept in their original, industrial form. The particular here is the arrangement of these structural elements in space, their relation to one another, and the unique way that this particular arrangement of rods and wires holds itself up.

![Маркс. Капитал: Критика политической экономии, 1872 год. [Первое издание] Маркс. Капитал: Критика политической экономии, 1872 год. [Первое издание]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!JT_y!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F53b5d1ce-d1fd-4278-a595-028fad586a0b_277x400.jpeg)